Mysterious missing weather stations and other lessons from tracking global heat

How can we show how much hotter it is than normal, every day, in every part of the world?

A colleague and I on the data team at The Associated Press built an interactive tracker to answer this question. In the process, we wrestled with more fundamental questions like what is “normal”? What does “nearest” mean? And why is nobody measuring the weather in Africa?

Mysterious missing weather stations

Satellites and weather stations track global temperature. We used both of these sources for our tracker. In this post, I’m going to focus on the latter.

Reading the weather each day, you might take for granted that we know the temperature of any point on Earth at any given time. But finding this information reliably over a 30-year period is complicated.

First, a myriad of public agencies, including NOAA, the military, and others, manage weather stations. Fortunately, one agency, the World Meteorological Organization, maintains a global network of stations that more or less report the same data.

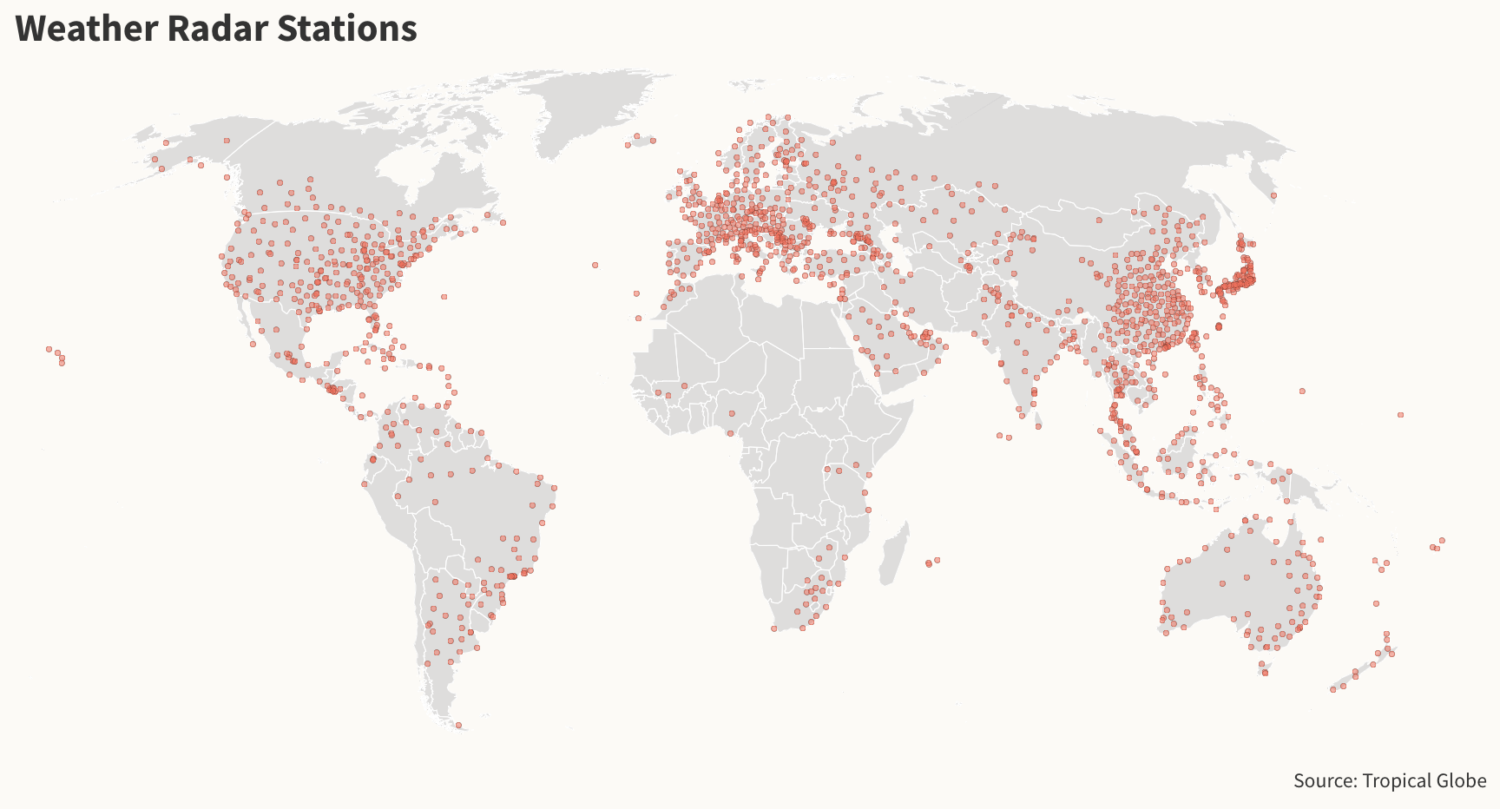

When I first plotted this network on a map, I thought I had inadvertently dropped data. Almost nothing showed up in Africa or South America.

I had stumbled upon a massive equity issue.

Many nations in the Global South lack functional weather stations. Africa, a continent with 1.2 billion people, has just 37 WMO weather stations . Meanwhile, the U.S. and E.U. combined have 636 weather radar stations for a population of 1.1 billion. Because of this disparity, US citizens were able to evacuate disasters like Hurricane Ida without major loss of life, while disasters such as Cyclone Idai hit Africa without warning.

Even among existing stations, we couldn’t collect enough data to depend on them. Many have fallen into disrepair. In Africa, only 1 in 5 stations met the WMO reporting standards in 2019. Among the many reasons for this are a lack of government support, staffing and technological infrastructure.

We filtered out hundreds of stations worldwide that haven’t recorded a blip of data in at least three years. Even the most reliable stations have a 3-5 day time lag between when the data is transmitted, and when it is processed and made available to the APIs we consume.

The heat tracker in action!

Pairing the stations with cities

Originally, we envisioned a sort of Billboard top 100 of hottest cities in the world right now. We found a dataset of the world’s 1,000 or so most populous cities. I wrote a Python script that matched each one to its nearest weather station. We filtered out any cities that didn’t have a station within 5 miles. Seemed simple enough.

But not really.

“Nearest” is not as straightforward a concept as it seems, in spatial analysis. To measure distance, we need to calculate it across a flat surface. Because the world is a sphere, and our books and screens are flat, we need projections to map between them. There are hundreds of projection functions ranging from basic rectangles (Mercator) to encapsulating the world in a twenty-sided die and unrolling it (Dymaxion). Any projection will have distortion, depending on what area you choose to focus. Certain projections are optimized for local places.

You can’t use one single projection to measure distances in all parts of the world. The best solution I could find is called Great Circle, or “Haversine” distance, which is measured in degrees as the distance around a sphere. It looks like the flight path of a plane.

This led to more problems, however. We had to establish a cutoff in degrees, which seemed nonsensical, or arbitrary at best.

And who decides where the “city center” is? City hall? The Central Business District? One paper identifies no less than 5 valid ways of deciding what is the “center.”

It turns out that nearly all WMO weather stations occupy an airport. Makes sense given how critical weather is to piloting. The distance of the center to the airport varies widely for most cities.

In the end, we decided it didn’t make sense to assign an arbitrary cutoff. Instead we let the stations stand on their own, and improved the map labeling and orientation with user controls like a search bar and geolocator.

What is a “normal” temperature?

After we were confident in our stations, we got down to the business of measuring the temperature. Absolute temperatures mattered little. We needed the deviation from average, or “normal” temperatures.

What is “normal?” Scientists have largely agreed it is the average of temperatures over a 30-year period. Technically, it’s not just an average — there is complex math to interpolate missing data points.

You also have to consider different time resolutions. You can average temperatures year by year, or month by month, or day by day. You can take the average of all the high temperatures or all the low temperatures, or work with all values recorded in each day.

So, which “normal” should we use?

Ideally, we would use a 30-year period from way in the past, before anthropogenic warming. Unfortunately, this was not possible at a global scale with existing data. The best the WMO provides is 1991-2020 normals. So what you see in the heat tracker, which still shows quite a bit of deviation from normal, is warming after much human-caused climate change.

I spoke with a climate scientist at NOAA to learn how to use their weather station data. Refreshingly, they thought it was as confusing to work with as I did. They reassured us that we could compare the average temperature for a single day to the monthly normal. It wasn’t exact, but was good enough.

We started with this, but then realized — for tracking heat, we cared about the hottest temperatures. We envisioned users checking this to see the impacts of recent heatwaves. So we subtracted the high temperature for the day from the “normal” — the average of high temperatures for that month over the 30-year baseline.

However, we needed one more step. Some days are quite hotter than others. That doesn’t necessarily mean there is an abnormal heat wave going on. Any time series will seasonal peaks and valleys in the overall trend line. To smooth out this daily noise, we compared the average high temperature from the past week with the average high for the month.

Updating the temperature every day

For the final setup, Our Python scripts query the National Center for Environmental Information’s common access API. Their normals endpoint returns monthly temperature normals given a list of stations.

We have a pre-filtered station list that we made, using another Python script. It contains reliable stations with long-term normals that also exist on a list of stations with reliable daily results from Common Access. We loop through all of our stations and get the latest temperature readings. We compare these to the normals we have stored for these stations.

Every day, we run these scripts via Gitlab actions. In our Gitlab repo, we store a .yml file that sets up the environment and runs the scripts each day. After the script runs, it pushes the output to a publicly readable S3 bucket.

The frontend is a React / Typescript app. We simply fetch the data from S3 and display it on a map. For the visualization, the map is built with Maplibre, and the line chart is rendered using SVG and D3.

Conclusion

Like all data viz projects, this one turned out to have many considerations I couldn’t have foreseen. But that’s what makes a project like this so fascinating.

The most important insight was the lack of attention to measuring climate and weather in the Global South. The biggest question I get about the project is “why isn’t x country on the map?” A host of political and historical reasons are behind this question. To ensure a safe and equitable climate future, it’s imperative that we focus more resources and attention on weather stations in underserved areas.